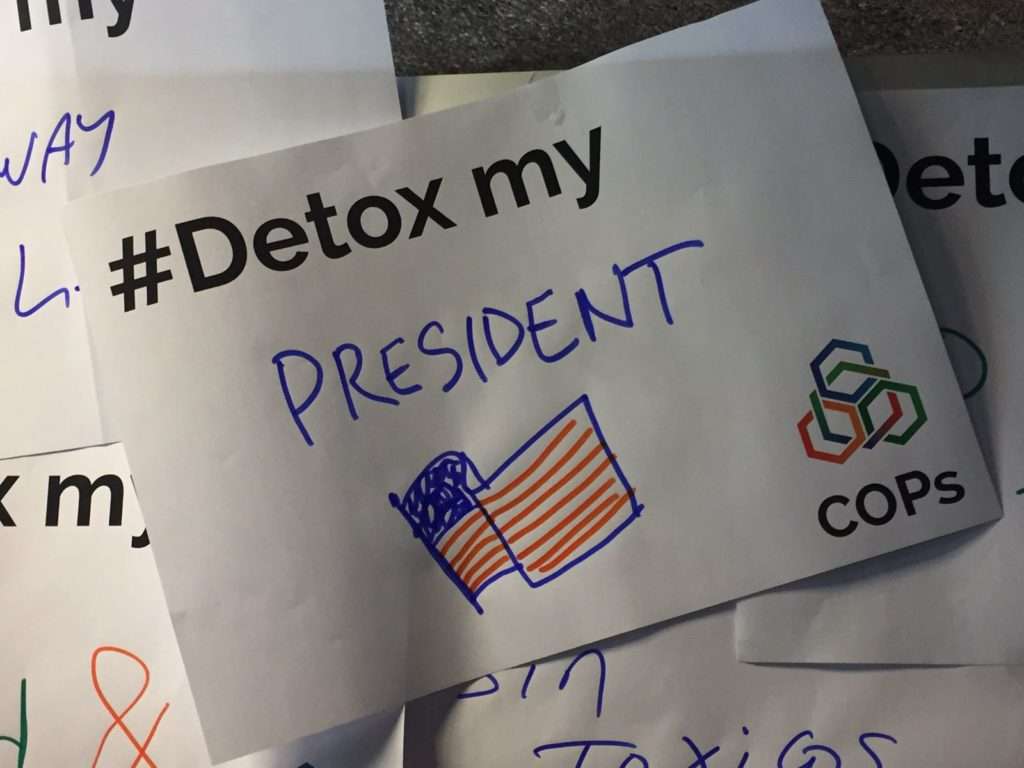

From April 24 to May 5, 2017, Parties to the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions (BRS) met for the Triple Conference of Parties (COP) in Geneva. The theme of this Triple COP was #detoxify. Surprisingly, of the 1,600 people who attended, very few actually had this theme on their agendas.

The national delegates to the Conventions of the Triple COP have a mandate to represent and defend their national interests and adopt decisions to implement the Conventions. The Secretariat of the Convention is a neutral facilitator of the discussion between these delegates. The private sector attends to persuade delegates that their national interests align with their industry’s interests. Civil society organizations (CSOs) round out this audience, acting as the conscience of the Conventions, reminding the delegates of the importance of defending the spirit and purpose of the Basel, Stockholm and Rotterdam Conventions: to detoxify our bodies and planet.

CIEL Environmental Health Director David Azoulay makes intervention at BRS Triple COP, May 2017

CIEL Environmental Health Director David Azoulay makes intervention at BRS Triple COP, May 2017

During my time at the Triple COP, I noticed that the role of the CSOs should not be underestimated. Of course, as observers, CSOs are not allowed to vote, but they are generally allowed to attend all negotiations, to observe, and in some cases to intervene during negotiations. In addition to their formal role as observers, CSOs raise Convention-specific concerns and assist many parties, in particular developing countries and countries with economies in transition, in both negotiation and implementation processes.

For example, right before the Triple COP started, the International POPs Elimination Network (IPEN) released a report on how toxic Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) end up in children toys because of toxic recycling. This report helped persuade Parties to oppose a proposed exemption under the Stockholm Convention that would have allowed banned chemical decaBDE to be recycled into new products. Similarly, CIEL published a report on how parties to the Bamako Convention could prohibit high sulfur fuels exports using the definitions of ‘hazardous waste’ under the Bamako and Basel Conventions and organized a side event on the topic. CIEL also played an important role in putting the issue of nano-waste on the Basel Agenda, by suggesting the idea to a group of countries including Switzerland, Zambia, and Jordan, and assisting in the drafting of a Conference Room Paper which was included in the secretariat work program.

Despite the efforts of CSOs, the conflicting interests of the delegates to the Triple COP led to some odd ‘victories’ – such as deciding to ban decaBDE and short-chain chlorinated paraffins under the Stockholm Convention, while simultaneously adopting such broad exemptions that industries are allowed to continue the use of these two chemicals for almost all of their existing applications. These exemptions are time-limited but still mean that these highly toxic, persistent, and bioaccumulative substances will remain in use for several years before being actually phased out.

Despite the efforts of CSOs, the conflicting interests of the delegates to the Triple COP led to some odd ‘victories’ – such as deciding to ban decaBDE and short-chain chlorinated paraffins under the Stockholm Convention, while simultaneously adopting such broad exemptions that industries are allowed to continue the use of these two chemicals for almost all of their existing applications. These exemptions are time-limited but still mean that these highly toxic, persistent, and bioaccumulative substances will remain in use for several years before being actually phased out.

Unfortunately, the role of civil society at the Triple COP is slowly being diminished. Many Parties do not appreciate the presence of non-State actors during plenaries and contact groups, and there are efforts to shut CSOs out of some of the most important decisions, and to overall reduce our role in the process. A clear example can be found in the efforts made by Russia, Iran, and India to keep non-State actors out of the negotiations and intercessional processes for the Rotterdam Convention (more details to come on this process in a follow up blog post) and the exclusion of civil society during the final negotiations on the listing of banned substances under the Stockholm Convention.

This is a very worrisome development, because CSOs are the only participants in the negotiation processes who are there with the sole purpose of protecting the integrity of the Conventions. Also, some parties rely on the assistance of CSOs to make their concerns heard, and with only State actors in the room, these smaller Parties might be bullied into submission by Parties that can afford to send and equip large delegations to attend these negotiations. Unfortunately, contrary to recognized best practices, limiting stakeholder engagement seems to be a pattern in UNEP-led processes over the past few years. This does not bode well for future multilateral environmental agreements and the detoxification of our planet.

Originally posted May 23, 2017