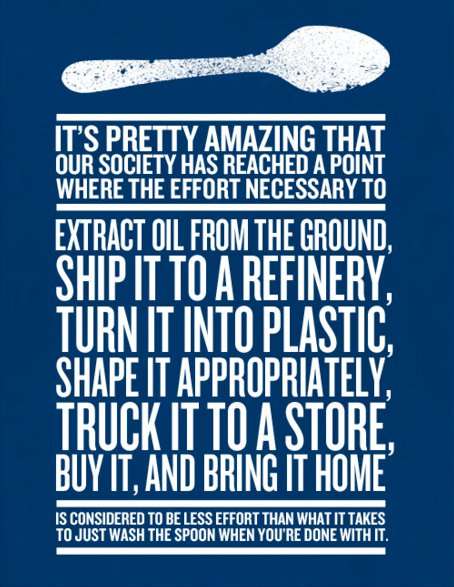

On a sleepless night scrolling through my Facebook posts, one mesmerizing image caught my attention. It said:

[“It’s pretty amazing that our society has reached a point where the effort necessary to extract oil from the ground, ship it to a refinery, turn it into plastic, shape it appropriately, truck it to a store, buy it, and bring it home is considered to be less effort than what it takes to just wash the spoon when you’re done with it.”]

While I am not a big user of plastic spoons, was I irresponsible because of the cup from which I sipped my coffee while walking to the office, for buying the plastic-bottled juice from the supermarket down the street, or getting my sushi lunch to-go in a plastic container?

Some plastic items are harder to get rid of than others. However, when I throw something in the recycling bin, I feel a bit relieved thinking that at least it will be recycled.

I have always thought that if my plastic were recycled, it would do no harm.

But that is just half of the story.

Have I ever known what is really in the plastic I was using? While I am aware that I should carefully read the ingredients of my shampoo to avoid toxic substances, it is simply not possible do that with all plastic products, including my toothbrush, my flip flops, or my cellphone cover.

Plastic additives that make products softer, more durable, or flame resistant can contain carbon-based substances that are or should be internationally banned because of their resistance to degradation and their adverse effects on human health and the environment, the so-called persistent organic pollutants, POPs. Some of those substances, such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), have endocrine disrupting properties as well (commonly known as endocrine disrupting chemicals or EDCs), meaning they can affect our hormonal system causing diseases such as hormones-related cancer, diabetes, and infertility.

If substances like POPs or EDCs are allowed in plastic and then plastic is recycled, it perpetuates a never-ending/uncontrollable circle of poison and harm.

Countries should make sure that harmful substances are neither produced nor recycled. However, governments’ decisions are often driven by commercial interests. For example, recycling toxic flame retardants PentaBDE and OctaBDE is still allowed worldwide, a misstep I witnessed at the latest conference of the parties to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.

But toxic recycling is not the only issue plaguing plastic. Plastic litter and microplastics are polluting our oceans, and plastic production facilities keep expanding. On ocean plastic pollution at least, there is some positive movement.

In May, I participated on behalf of CIEL in the international conference of more than 180 countries. There, parties to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants and the Basel Convention on transboundary movement of waste decided to begin working on marine plastic litter and microplastics. This should include the POPs and endocrine disrupting components of plastics.

We are committed to engage in and push for global actions and policy to address plastic pollution at its source and prevent the petrochemical industry from poisoning both the negotiations for better protections and our health.

By Giulia Carlini, Staff Attorney

Originally posted July 8, 2017