The year 2020 was supposed to be the “super year for nature.” Many people around the world were expecting new, ambitious goals to protect our oceans and biodiversity and to better regulate chemicals and waste. Events were scheduled and hopes were high. After all, this decade is the last real chance to reverse biodiversity loss and restore nature. But everything screeched to a halt with the COVID-19 crisis.

While media portrays the environmental impacts of the virus as a silver lining, the reality is that these effects only appear to be favorable — and they will not last long. Some governments are using the pandemic to lower environmental standards and bail out polluting industries. David Boyd, Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, said that these responses are “irrational, irresponsible, and jeopardize the rights of vulnerable people.” And while parts of the world have begun to “build back better,” the rest of us have a choice: restore the failing and destructive system or flip a “green switch.”

Progress Toward International Chemicals and Waste Management

In 2002, the World Summit on Sustainable Development set a global goal to minimize the adverse human health and environmental effects of producing and using chemicals by 2020. This was reaffirmed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Since the 2002 Summit, the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) was created to achieve this target, and the International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM) was established to continually review SAICM and its progress.

The problem is that SAICM’s current framework expires in 2020, and it’s clear that the intended goal will not be achieved in time. Chemicals’ impact on people and the environment has never been deadlier or more destructive. (In 2016 alone, 1.6 million lives were lost due to the direct impacts of just a small subset of chemicals.) Many countries lack basic management capacity to, for example, implement pollutant release and transfer registries or inspect waste disposal facilities.

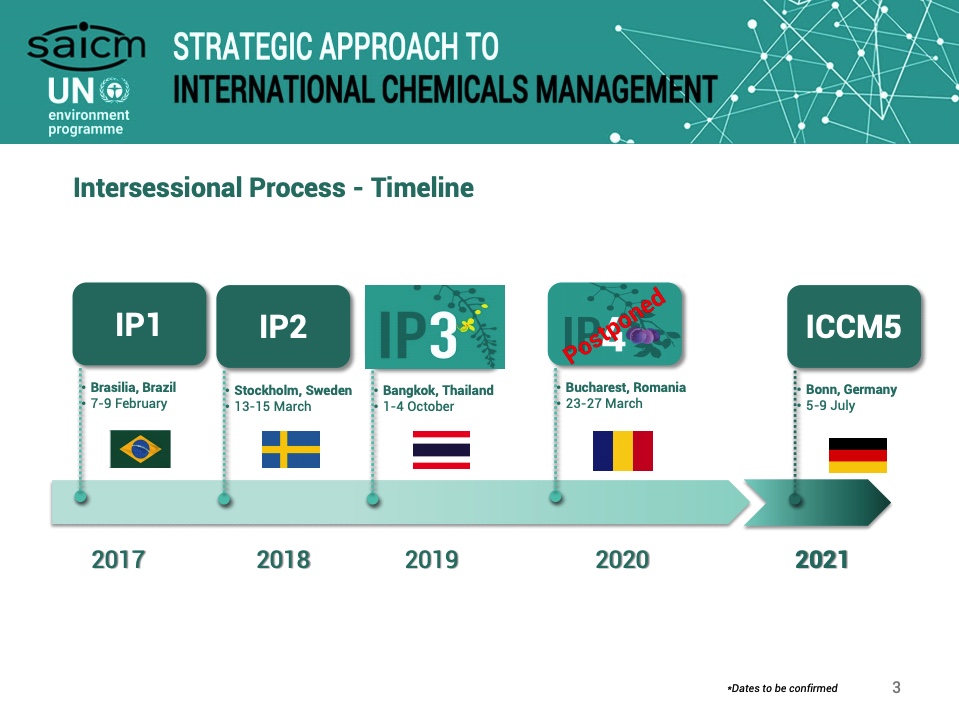

Given the discrepancy between where the international community is and where they want to be on chemical and waste management, there is still much work to be done after 2020. To address this, an intersessional process has been created to continue the work of SAICM after it expires.

For this framework to be effective, two things need to occur: First, a more coherent and defined approach to measuring results must be established. Second, there should be a funding increase to minimize the adverse impacts of chemical production and use successfully. To that end, a Technical Working Group has been established. Many stakeholders, including the European Union and the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), are suggesting to upgrade SAICM to “SAICM 2.0” and to build an “enabling framework” with measurable, time-bound targets, indicators, and milestones. CIEL and IPEN will soon introduce a proposal to significantly increase funding levels devoted to chemicals management projects in developing and transition countries while implementing the “polluter pays” principle.

While progress has been made on establishing the framework, there is still more work to be done, and COVID-19 is standing in the way. The Fourth Meeting of the Intersessional Process (IP4) was scheduled for March 2020. Part of its agenda was to translate objectives into concrete measures, but that meeting was postponed indefinitely. Similarly, the next International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM5), the deciding body for the new framework, was scheduled for October 2020, but will take place in July 2021. A lot can happen in the next twelve months — but it is vital that the international community stays determined in their progress toward a new chemical and waste framework.

Alliances to Driving Ambition

Fortunately, the proposed chemicals and waste framework was not the only reason to be hopeful for 2020. Some specific countries are also driving ambition. Uruguay and Sweden, for example, have taken the initiative in forming a High Ambition Alliance on Chemicals and Waste (hopefully, the first of many more!). This Alliance comprises ministers and senior representatives from governments, intergovernmental organizations, industry, and civil society, committed to working together to address the risks that certain chemicals impose on health and the environment. Its aim is to facilitate the adoption of an ambitious, global deal on the management of chemicals and waste. With enough pressure and persuasion, more governments and stakeholders will hopefully join the Alliance to strengthen chemicals regulation in 2020, and beyond.

Looking Ahead

While there is much to anticipate in chemical and waste management, it is also necessary to examine responses to COVID-19. In many areas, the global community is responding by taking several steps backward, rather than steps forward.

Global trends include things like plastic piling up, waste management systems being overwhelmed, mounting health hazards due to the mass use of disinfectants, and discontinuation of recycling programs. Specific sectors are also capitalizing on the pandemic. For example, the plastic industry has successfully lobbied governments to delay or remove plastic bag bans, while oil companies are ramping up plastic production to salvage the lost profits from the sharp decline in fuel demand. Countries are implementing legislative and regulatory measures. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) weakened the Toxic Substances Control Act to appease a number of chemical and petrochemical manufacturers. The United Kingdom postponed a ban on specific single-use plastic products, which had been scheduled for April. Italy postponed its tax on plastic, which was supposed to go into effect during the spring.

These responses are incommensurate with commitments to working toward better waste and chemical management. However, our responses to crises have the potential to change the future. Despite what many claim, the global pandemic is not “healing our planet.” We must do that. Ultimately, we have a choice to make: Do we want to go “back to normal” — the same normal that likely spread the virus in the first place — or do we want to move forward? Now more than ever, it’s on us to embrace an alternative, greener path toward a more resilient and sustainable future.

By Ekaterina Mikhaylova, Legal Intern, Geneva

Originally posted on July 23, 2020