European governments have the opportunity (and the legal duty) to promote public participation in the implementation of climate action, yet some fail to do so.

The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement was celebrated not only for bringing together all countries around the urgency of climate action, but also for emphasizing the importance of people-centered climate action. People-centered climate action promotes people’s rights and involves them in the process of designing climate policy. The preamble of the Paris Agreement stresses the importance for governments to respect, promote, and consider their human rights obligations when taking action to address climate change, and article 12 of the agreement emphasizes the need to improve public participation and access to information.

Ensuring the effective and meaningful participation of the public in climate-related decision-making is critical to ensuring that policies are designed in a way that respects the rights of communities and contributes to gender equality and social justice. It’s also more effective: It strengthens public support for climate measures and delivers better results in reducing emissions and improving communities’ resilience to climate change.

The international community has the opportunity this year to reinforce this principle as it fleshes out the rules for putting the Paris Agreement into action in 196 countries. These implementation guidelines offer many opportunities for governments to reaffirm the need for public participation in climate policies at both the international and domestic levels.

For instance, the decisions adopted this year could stress that countries must develop their future national climate commitments through a transparent and participatory process. They could also define opportunities for civil society to help monitor governments’ actions to ensure they are honoring their commitments. And as governments elaborate rules for international trading in carbon credits, they should ensure that local communities participate throughout the planning and development of any project promoted through these schemes and offer adequate remedies when this is not the case.

But for 46 countries from Europe and Central Asia, as well as for the European Union itself, promoting access to information, public participation, and access to remedies in international climate governance is not merely good practice. It’s also a legally binding obligation.

All these countries have ratified the Aarhus Convention on Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making. In unequivocal terms, the Convention stresses that these 46 governments and the EU must promote these three principles in international environmental decision-making. In other words, the countries that have ratified the Aarhus Convention must not only respect the right of the public to participate in climate negotiations, but also champion the recognition of this right in the decisions adopted in the UN climate conferences.

So are they? To assess whether European governments actually respect their Aarhus Convention obligations in the ongoing climate negotiations, we compared the positions they adopted in their last written contributions and during the last climate meeting in May 2018 with key aspects of the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

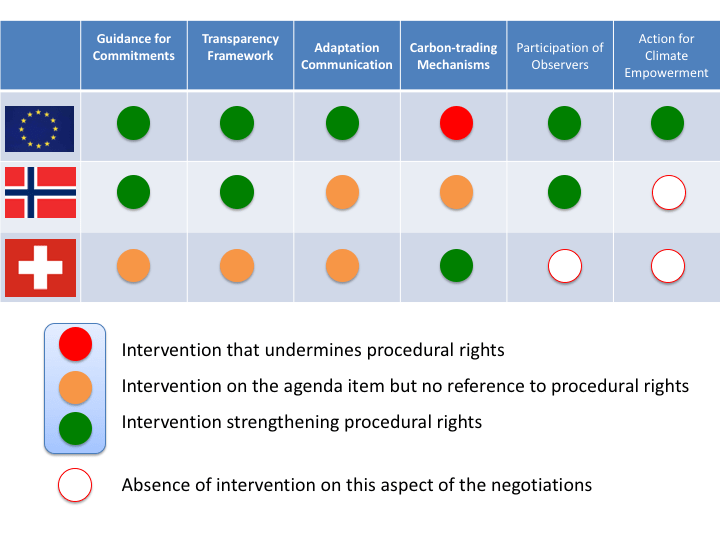

Below, I summarize our findings on three key actors that play active roles in the climate negotiations: the EU (negotiating on behalf of its 28 member states), Norway, and Switzerland. We assess whether the principle of environmental democracy is reflected in any proposal put forward through the written or oral interventions of these three players (though this does not necessarily reflect the quality of those proposals otherwise).

- In the majority of the negotiations to which it contributed, Norway emphasized that climate governance must involve civil society.

- In most discussions, the European Union referred to the role and value of civil society in the design and implementation of climate policies. Yet during negotiations related to the carbon-trading mechanisms established under the Paris Agreement, the EU intervened to downplay the importance of social safeguards.

- And while putting forward elaborate proposals on most issues discussed during these meetings, Switzerland failed in most cases to refer to the role of civil society, thereby falling far short of promoting public participation in the implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement.

At the beginning of September, climate negotiations will resume in Bangkok, offering another chance for all countries — and in particular those that are Parties to the Aarhus Convention — to flesh out and support proposals that would give life to the “Paris spirit,” that of people-centered climate action.

For Switzerland and the EU, this is a matter not just of good governance, but also of correcting their track record at the recent climate talks and of complying fully with their legal obligation to promote environmental democracy in international negotiations.

By Sébastien Duyck, Senior Attorney

Originally posted on August 21, 2018