Industrial activities have enabled the creation of thousands of new industrial chemicals that do not exist in nature. Global growth in chemical production continues at an alarming pace, nearly doubling between 2000 and 2017. In a 2019 report, the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) estimates that sales will double once again before 2030, with growth primarily driven by emerging economies.

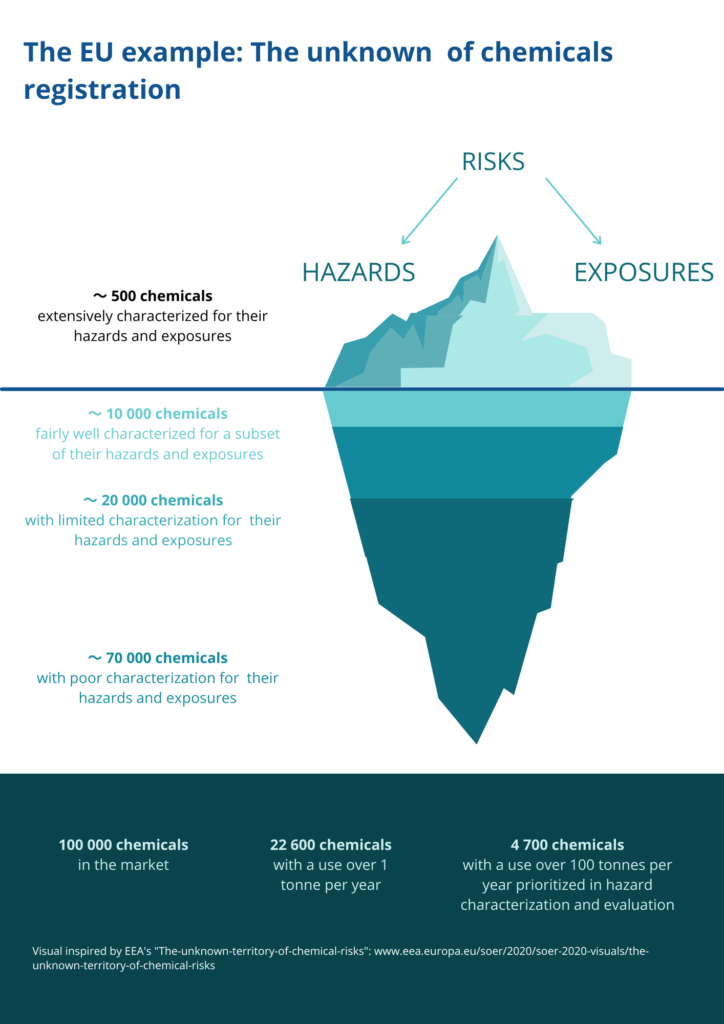

Due to the pace at which chemicals are being developed, many enter the market without a prior comprehensive analysis of the hazards and risks they pose to the environment and human health. To address the consequences for human health and to respond to the anticipated growth in the sector, there is a need for more robust international chemicals governance.

The purpose of this tutorial is to introduce at a high-level, the challenges that chemicals pose and what is necessary to achieve effective chemicals governance.

The unique challenges posed by chemicals

Four features are critical to understanding the governance challenges that chemicals pose.

- Harm: Hazardous chemicals can be linked to various negative health impacts with delayed onset (e.g., reproductive harms and illnesses). These impacts may only emerge after specific circumstances, including interactions with other chemicals and individual and environmental factors.

- Travel: When in liquid or gaseous forms, chemicals cannot be contained to a limited area and will travel through air and waterways to destinations far from their initial release. Practically, this can lead to bioaccumulation and biomagnification in communities and affected ecosystems.

- Ubiquity: Due to the high concentrations of chemicals in many parts of the world, people can’t avoid exposure to toxic chemicals. Their omnipresence means that exposure can — and does — occur throughout an individual’s lifetime, beginning in utero.

- Information asymmetry: While chemical manufacturers have/hold information on the chemicals they produce, that is not automatically passed on to the value chain: retailers and consumers are often victims of a lack of transparency. There can be significant gaps in data on chemicals hazards and risks, as shown by a UCSF study that found evidence of dozens of mystery chemicals whose sources and uses were unknown.

If the objective of chemicals governance is to establish rules to prevent and minimize the harmful impacts of chemicals, with the aim of protecting people’s health and the environment, it is essential to develop control systems. When properly designed, these systems will prevent chemicals from becoming a burden for countries, avoid harm, and promote safe chemicals.

Once governments and institutions establish these norms, there is a greater incentive for companies to move away from toxic substances. The shift will encourage the research, development, and innovation of new, safer chemicals, save costs, and benefit human health and the environment.

Ten pillars for effective chemicals governance

The prerequisite for effective chemicals governance is the creation of administrative infrastructure. Such infrastructure needs to include creating government institutions with clearly defined responsibilities to execute basic functions. It can be designed as either a chemicals control authority within a larger government entity or a standalone institution. Regardless of the design, the institutions tasked with chemicals governance require adequate resourcing to fulfill their duties.

States must follow ten basic principles to establish effective chemicals governance.

Before Entry onto the Market: Chemicals Control

- Make determinations: States need a mechanism to decide what chemicals could be available for manufacture and import on their market/country and how to introduce them.

- Access to reliable information: In determining what chemicals to introduce, states and other stakeholders need access to reliable information about the hazards and risks associated with each. Information may be available through existing databases, including REACH, OECD eCHEM, UN GHS list of CMR substances, etc.

- Ability to issue bans: Should an institution determine that a chemical poses too great of a hazard or risk, they must be able to ban it before it enters the market.

- Flexibility to restrict: If certain chemicals cause concern but their use is still justified, states need to be able to issue restrictions, essentially approving their entry into the market, but limiting their uses.

Once Available for Sale: Manufacture, Distribution, and Use

- Design and disseminate information: States and industry must work together to develop consumer-facing labeling that includes information such as the permissible uses of chemicals. They must also develop plans to distribute that information to the public.

- Meet existing obligations: As chemicals enter the market, states must work to ensure that they continue to meet their treaty obligations that may limit or restrict the manufacturing, distribution, or use of chemicals.

- Monitor the exposure: States must develop systems to monitor whether chemicals are contaminating the environment and potentially harming populations (e.g. through water, soil, and consumer products).

- Ensure continued safety: Once a chemical enters the market, it is of paramount importance for it to be safe for human health and the environment. Institutions need to create controls, including inspections and enforcement mechanisms, to ensure the safe production and use of chemicals.

After Chemicals are Used: Manage the End of Life

- Prevent new toxic waste: Public and private entities need to be able to dispose of chemicals in a safe manner that does not put public health or the environment at risk. Institutions must develop adequate waste management infrastructure.

- Clean legacy pollution: Since toxic legacies continue to exist, states need to develop and execute plans to clean up legacy pollution, ideally using the polluter pays principle.

Useful resources on chemicals governance:

General:

- Briefing from UNEP for high-level officials or new audiences

- Benefits of Chemical Control (2019)

- Options from UNEP for organizing national land institutional infrastructures to govern the placement of chemicals on the market, includes templates for framework law, recommendations for sustainable financing, and access to budget allocation processes.

- Guidance from UNEP on assisting governments in chemicals control implementation

- Complementary Guidance to LIRA (2019)

- National Chemicals Control Authority: Structure and Financing

- Risk Reduction Tools for Chemical Control

- Mechanisms to Ensure Compliance with Legislation on the Control of Chemicals

- Complementary Guidance to LIRA (2019)

- Toolbox from Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC) designed to help countries to identify the most appropriate and efficient national actions to address specific national problems related to chemicals management and identify simple cost-effective solutions.

- Case studies from European Environment Agency (EEA) examining early warnings about chemicals such as Benzene, Asbestos, PCBs, DDT, and BPA. Includes information about what was used, or not used, to reduce hazards. Includes details that describe the resulting costs, benefits, and lessons for the future.

- An assessment from UNEP of the current state of knowledge of the economic costs of inaction on the sound management of chemicals, includes information about the need for enhanced political action to defray costs.

- Key Messages from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UNEP on human rights obligations and responsibilities for preventing and remedying the harmful effects of hazardous substances

- Guidance from the Swedish Chemicals Agency (Keml) on issues related to chemical control, including setting up efficient systems, legal and voluntary tools for risk reduction, and enforcement of legislation.

African Region-specific Tools:

- A regional assessment report and data from Member States issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) concerning the African Region

- A detailed project from UNEP, WHO, and Africa Institute Environmental Observatories project that includes two calculators. The first is based on risk and vulnerability, generating risk scores based on several factors and certain assumptions, thus enabling governments to prioritize how to regulate chemicals if resources are limited. The second looks at the economic cost of inaction if chemicals are not managed properly, with costs measured in “Disability Adjusted Life-Years”* (DALYs).

* “Disability Adjusted Life-Years” (“DALYs”) are defined as the years of productive life lost either to greater impairments due to the disease burden of chemicals, lower expected IQ scores, and economic extrapolations based on these, or to early death. DALYs are a controversial metric of harm for how they treat disability as a universal concept without attention to context or disability rights, for their use of IQ scores in reasoning performances, and for economic extrapolations for seemingly emphasizing peoples’ value to society purely on the basis of their labor and spending. While critiques are valid, DALYs can present one useful comparative benchmark to demonstrate the cost of chemical mismanagement and the benefit of sound management. DALYs should not be understood to represent the totality of harm.